September 7th: A Nation Can Never Be Grandiose By Forging Its Own History

September 7th: A Nation Can Never Be Grandiose By Forging Its Own History. September 7, 1822, marks one of the most famous dates in Brazilian history. The scene is instantly recognizable: Dom Pedro I, the prince regent, on the banks of the Ipiranga river, his sword raised, proclaiming the "Cry of Independence or Death!"

FACES AND FACTS

Everton Faustino

9/6/20255 min read

September 7th: A Nation Can Never Be Grandiose By Forging Its Own History

September 7, 1822, marks one of the most famous dates in Brazilian history. The scene is instantly recognizable: Dom Pedro I, the prince regent, on the banks of the Ipiranga river, his sword raised, proclaiming the "Cry of Independence or Death!" This is the narrative we learned in school, immortalized on the grand canvas of Pedro Américo and in the anthem of independence. But while national memory celebrates this heroic scene, history invites us to look beyond the myth and confront an uncomfortable truth: a nation can never be grandiose by forging its own history.

Brazil's independence, more than a singular, dramatic act, was a complex process filled with intrigue, competing interests, and figures that the official narrative relegated to the background. By deconstructing the legend of the Cry of Ipiranga, we discover that the construction of our national identity is as fascinating as the contradictions that shaped it.

The Myth of the Hero vs. The Reality of the Tired Mule

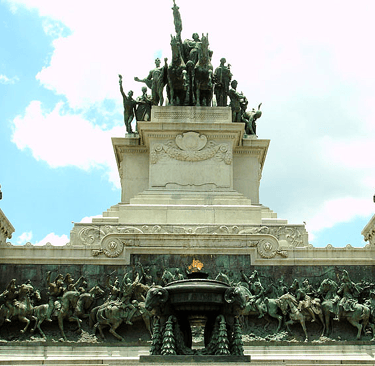

The painting "Independence or Death!" (1888) by Pedro Américo is perhaps the single greatest source of the date's romanticization. In it, we see an imposing Dom Pedro on a powerful steed, surrounded by a guard of honor in impeccably clean uniforms, with gleaming swords drawn. The scene is worthy of a European epic, custom-made for the idealization of a new empire.

However, historians, based on accounts and documents from the era, offer a far less glorious version. Dom Pedro was not on a stallion, but likely on a mule, an animal better suited for the long, arduous journeys of that period. Instead of a guard of honor in dress uniform, he was accompanied by a travel-worn entourage, tired and dusty. To add a touch of humanity to the scene, there are indications that the prince himself was suffering from intestinal issues, a result of the exhausting trip. The famous phrase "Independence or Death!" also lacks any official written record. It is more likely a symbolic construct, a dramatic element added later to lend grandeur to the moment and solidify the hero's figure.

This discrepancy between myth and reality does not diminish the importance of September 7th. On the contrary, it shows us how historical memory was deliberately constructed at the end of the 19th century, a time when Brazil, already a republic, sought a narrative of unity and greatness to legitimize its own national project.

The Protagonists Behind the Scenes: Leopoldina and José Bonifácio

The history of independence, when centered solely on Dom Pedro, makes crucial figures who acted behind the scenes invisible. The role of Princess Leopoldina is one of the most underrated and, paradoxically, one of the most decisive.

In 1822, while Dom Pedro was traveling through São Paulo, Leopoldina served as the interim regent in Rio de Janeiro. She was the one who received the latest orders from the Portuguese Courts, which demanded Brazil's submission and the prince's immediate return to Lisbon. Accompanied by strategic advisors like José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva, the princess did not hesitate. On September 2, aware of the inevitability of a break, she signed the decree that formally separated Brazil from Portugal and sent a letter to Dom Pedro, advising him to proclaim independence.

Leopoldina and her council's decision was not impulsive. It was a calculated political move, a stateswoman's act by a woman with a solid political education. This is why many historians consider her the "mother of Independence." The Cry of Ipiranga was the materialization of a decision that had already been made days earlier in Rio de Janeiro, under the leadership of a woman whom official history, for a long time, left in the shadows.

The Republic and the Appropriation of September 7th

The Proclamation of the Republic on November 15, 1889, created a symbolic problem for the new regime. How could it celebrate Independence, a symbol of national unity, when it had been proclaimed by an emperor? The solution was the reinterpretation of the date.

The military and the republican elites could not simply erase September 7th. Instead, they kept it as a national holiday but detached it from the figure of Dom Pedro I. The focus shifted to the Brazilian people and the military, who were now presented as the true guardians of the nation. The civic-military parades, which became the hallmark of the celebration, reinforced this new narrative, in which the Army was the natural heir to the spirit of freedom.

The Republic appropriated the date to legitimize its own existence, building a foundational myth that connected the political independence of 1822 to the "social independence" of 1889. This discourse, however, ignored the exclusionary manner in which the new regime was born.

The Myth of the Republic: The Popular Will That Never Existed

The official narrative, constructed throughout the 20th century, presents the Republic as the fulfillment of popular desires. But, like September 7th, November 15th is also a myth. The Proclamation of the Republic was not a popular movement. It was a military coup orchestrated by dissatisfied elites, led by Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca.

The Brazilian people, for the most part, did not participate in the process and, to a large extent, did not even understand what was happening. Accounts from the time indicate that the population, which saw Dom Pedro II as a stable and respected figure, observed the event with indifference, believing it was just another ministerial change. The Republic was born without popular consent, based on a project that, in practice, maintained exclusion. The so-called Old Republic (1889–1930) consolidated a restricted political system, with voting limited to less than 5% of the population and power held by rural oligarchies.

The republican myth, therefore, is a contradiction. The discourse of "government of the people" stood in stark contrast to a reality of exclusion, where elites controlled the country's politics and decisions. September 7th, when reinterpreted, served as a useful symbol to cover up this fracture between the heroic narrative and historical reality.

The Path to a More Just History

September 7th is a date of great importance, a moment to celebrate national sovereignty. But more than a civic holiday, it should be an opportunity for historical reflection.

By confronting myths with facts, we recognize that history is not just a sequence of events but a narrative that is often constructed and manipulated to serve political purposes. Demystifying the Cry of Ipiranga, recognizing the agency of Leopoldina and other historical figures, and understanding the elitist origins of our Republic is the first step toward a more honest history.

A truly grandiose nation does not forge its history to create perfect heroes but embraces it in all its complexity, with its flaws, its contradictions, and its forgotten protagonists. By doing so, we do not diminish our past; we make it more human, more real, and, above all, more truthful. Only then can we build a more inclusive future, based not on myths but on a clear understanding of who we were and who we want to be.