How Brazil’s Aristocracy Turned Freedom into Marginalization

How Brazil’s Aristocracy Turned Freedom into Marginalization. The Golden Law, signed by Princess Isabel, granted no compensation to slaveholders. For Brazil’s powerful coffee-based landowners, the decree meant immediate and irreversible economic losses. These elites, once the backbone of the imperial economy and political structure, felt betrayed by the monarchy. Many historians see this resentment as the key factor behind the aristocracy’s support for the republican coup in 1889.

FACES AND FACTS

Unveiled Brazil

10/19/20254 min read

From Abolition to Republic: How Brazil’s Aristocracy Turned Freedom into Marginalization

From Celebration to Exclusion

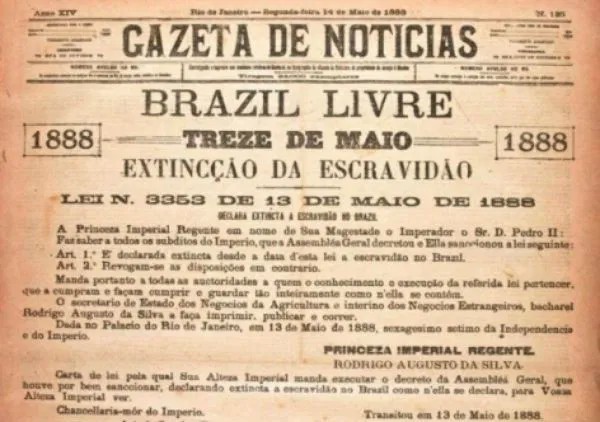

On May 13, 1888, Brazil celebrated with joy the signing of the Golden Law (Lei Áurea), which officially abolished slavery. The country — the last in the Western world to end forced labor — seemed finally ready to enter a new moral and social era. Yet little more than a year later, in November 1889, the Empire collapsed, and the Republic was proclaimed by a coalition of military officers and landowners.

The timing between abolition and the fall of the monarchy raises a question that still echoes today:

Was the marginalization of Brazil’s Black population an accidental outcome — or a deliberate act by an aristocracy seeking revenge for the loss of its privileges under the Golden Law?

Economic Impact of Abolition on the Rural Aristocracy

The Golden Law, signed by Princess Isabel, granted no compensation to slaveholders. For Brazil’s powerful coffee-based landowners, the decree meant immediate and irreversible economic losses.

These elites, once the backbone of the imperial economy and political structure, felt betrayed by the monarchy. Many historians see this resentment as the key factor behind the aristocracy’s support for the republican coup in 1889.

In this sense, the Republic was born out of resentment — a reaction by elites who had lost their free labor force and sought to rebuild their political power under a new system.

The Moral Courage of Princess Isabel

The signing of the Golden Law was an act of extraordinary moral and political courage. As regent in her father’s absence, Princess Isabel faced immense pressure from Parliament and the rural elite, fully aware that her decision could cost her family the throne.

Guided by Christian and humanitarian convictions, she considered slavery a moral stain on the nation. Her act earned praise from Pope Leo XIII, who commended her for a “great work of redemption.” Isabel signed the law without hesitation, even knowing it would alienate the same aristocracy that sustained the Empire.

Her decision was one of conscience, not convenience — a defining moment that immortalized her as “The Redeemer”, representing a monarchy striving to align itself with principles of social justice and human dignity.

From the End of Slavery to the Absence of Citizenship

While the Empire abolished slavery, the Republic failed to transform former slaves into citizens.

No public policies were created to integrate freed people into the labor market, and there were no education or land reform programs.

The absence of institutional support pushed Brazil’s Black population into the margins — forming early slums, working low-paid jobs, and facing systematic criminalization.

For many analysts, this omission was not accidental but a strategic political choice by the republican elite — a way to maintain control and prevent the empowerment of the newly freed population.

The Interrupted Imperial Project

Supporters of the monarchy argue that the Empire was preparing to implement new social inclusion policies, inspired by Christian ethics and Princess Isabel’s humanitarian outlook.

Contemporary records from the Council of State reveal discussions on promoting free labor, land access, and expanding public education.

The fall of the Empire thus interrupted a potential gradual transition toward a more inclusive society. The Republic, prioritizing political stability and regional oligarchies, left the freed population without representation or civil rights.

Erasing May 13 and Rewriting History

In the early republican decades, May 13 — once a celebrated national date — was gradually abandoned.

Its association with Princess Isabel and the imperial legacy made it politically inconvenient for a regime eager to assert its own legitimacy.

By the 20th century, intellectuals and social movements began to reinterpret the abolition — no longer as an act of benevolence, but as an incomplete gesture that freed people without offering real opportunities or dignity.

The Rise of November 20 and the Reframing of Memory

In the 1970s, November 20 — the death date of Zumbi dos Palmares, leader of a fugitive slave settlement — was proposed as a new symbol of Black resistance.

For activists, it represented autonomous struggle, in contrast to the “white” and “imperial” narrative of May 13.

However, scholars point out that this shift carried ideological consequences:

It reinforced the symbolic break with the Empire;

It centered history on racial conflict and armed resistance;

It diminished the legacy of abolitionists tied to the State, the Church, and the Monarchy — such as André Rebouças, José do Patrocínio, and Princess Isabel herself.

Furthermore, historical records show that Zumbi himself held slaves in Palmares, complicating his image as a liberator.

His elevation, therefore, can be interpreted as a political symbol rather than a purely historical one.

Competing Visions: Ideology and Identity

The conservative view sees the replacement of May 13 by November 20 as part of a republican and ideological effort to erase the civilizing role of the Empire and deny the Christian and monarchical influence behind abolition.

The progressive perspective, on the other hand, views November 20 as a necessary correction — emphasizing Black resistance and exposing the persistence of structural racism after 1888.

Yet both interpretations converge on one point: abolition did not bring full citizenship.

The difference lies in who bears responsibility — the Empire that fell too soon, or the Republic that inherited and perpetuated exclusion.

Conclusion: Interrupted Freedom

More than a century later, Brazil still grapples with the consequences of its transition from slavery to freedom.

Abolition was a legal milestone, but it did not translate into social equality.

The Republic — born from an elite’s resentment — preserved structures that marginalized millions.

While November 20 remains an important symbol of resistance, it should not erase the significance of May 13, the day when the Brazilian State formally recognized human dignity above property.

Between memory and ideology, the story of Brazil’s abolition continues to reflect the power struggles that shaped the nation — and still define what freedom truly means.

SEO Keywords:

Brazilian abolition of slavery, Golden Law, Princess Isabel, Empire of Brazil, Brazilian Republic, rural aristocracy, Zumbi dos Palmares, Black Consciousness Day, Brazilian history, social marginalization, abolitionist movement, agrarian elite, imperial to republican transition.