Tiradentes: Martyr of the Minas Conspiracy or Manufactured Hero?

Tiradentes: Martyr of the Minas Conspiracy or Manufactured Hero? Joaquim José da Silva Xavier, nicknamed Tiradentes (Tooth Puller) due to his profession as a dentist, stands as a central figure in Brazil's pantheon of national heroes.

Everton Faustino

4/21/20256 min leer

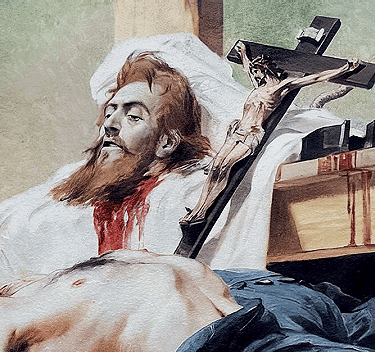

Pedro Américo represents in his painting the dark desires of an illegitimate government.

His image, frequently depicted as a bearded man with a suffering countenance, resonates through history books as the martyr of the Minas Conspiracy (Inconfidência Mineira), a conjuration that sought the independence of colonial Brazil from Portugal in the late 18th century. However, the story of Tiradentes is far more complex, filled with nuances that challenge the traditionally taught heroic narrative.

Although the Minas Conspiracy occurred during a period when Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the Marquis of Pombal, wielded significant influence in Portuguese politics, he had already been removed from power in 1777, seven years before the conspiracy was uncovered. Therefore, the persecution of Tiradentes and the other conspirators was not a direct initiative of Pombal. The Portuguese Crown's motivation to suppress the movement lay in defending its economic interests and maintaining control over the rich Captaincy of Minas Gerais, whose gold production was crucial for the kingdom's finances. The Conspiracy, with its ideals of liberty and autonomy, represented a direct threat to this dominion.

Far From a Hero.

Interestingly, Tiradentes was not instantly elevated to the position of national hero after his execution on April 21, 1792. During the imperial period and much of the Old Republic, the Minas Conspiracy was viewed with a certain ambivalence. Some considered it an isolated revolt of local elites, while others feared the destabilizing potential of separatist movements. It was only during the First Republic (1889-1930), more specifically from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that the figure of Tiradentes began to be reinterpreted and promoted as a symbol of the struggle for freedom and national identity. Decree No. 155-B, dated January 14, 1890, officially established April 21st as a national holiday in memory of Tiradentes, marking a crucial point in this heroic construction.

The execution of Tiradentes was a brutal and public event, intended to serve as an example to deter future attempts at insurrection. Convicted of lèse-majesté (treason), he was hanged in Rio de Janeiro, in Campo de Santana (now Praça Tiradentes). His body was quartered, and his limbs were scattered throughout different locations in Minas Gerais where there were supporters of the Conspiracy. The house where he lived was burned down, and the ground was salted in an attempt to erase any trace of his existence and memory.

However, historical records and recent research reveal important nuances that contrast with the simplified image of Tiradentes as a unanimous and idealistic leader. Documents from the time indicate that he was an alferes (a junior military officer) with financial difficulties and a certain degree of instability. His participation in the Conspiracy seems to have been more as a popular agitator and spokesperson for the ideas of other members of the Minas elite, such as intellectuals and indebted miners. Contrary to the image of an intellectual leader, Tiradentes was considered by some contemporaries to be a talkative and even naive individual.

The ascent of Tiradentes to the pantheon of national heroes during the First Republic did not occur by chance. In a period of consolidation of the new republican regime, which sought to distance itself from the recently overthrown monarchy, the figure of a martyr for independence proved extremely useful. Tiradentes, a "man of the people" (despite his military rank) who had sacrificed himself against the oppression of the Portuguese Crown, fit perfectly into the narrative of a republic built on the ideals of liberty and equality, in contrast to the monarchical period. By exalting Tiradentes, the republican regime sought to legitimize its own existence and create a unified sense of national identity around a "popular" hero who fought against the Portuguese "oppressor," overshadowing, to some extent, the complex history of the monarchical period and its own actors.

The Minas Conspiracy was motivated by a confluence of factors, the main one being the growing dissatisfaction with the oppressive fiscal policy of the Portuguese Crown. The metropolis, increasingly in need of resources to sustain its expenses, intensified the collection of taxes on the rich gold production of the Captaincy of Minas Gerais, culminating in the dreaded "derrama" – a compulsory collection of overdue taxes, even if it meant confiscating the colonists' property. This scenario of economic exploitation, coupled with the spread of Enlightenment ideas that preached liberty and autonomy, and the example of the independence of the Thirteen Colonies of North America, fueled the desire of a local elite, composed of intellectuals, clergy, miners, and some military personnel, to break ties with Portugal and establish an independent republic in Minas Gerais.

Coincidence? The Martyr's Image

The association of Tiradentes's bearded and suffering image with the figure of Jesus Christ, especially during a period close to Easter, is widely considered intentional and part of a strategy to construct a martyr for the republican cause.

Historical studies and facts supporting this interpretation include:

The context of the Proclamation of the Republic: After the fall of the monarchy in 1889, there was a need to build a republican national identity, seeking symbols and heroes that would contrast with the figure of the emperor and the monarchical period. Tiradentes, a "martyr" who fought against the "oppression" of the Portuguese Crown, fit perfectly into this role.

The absence of contemporary iconography: There are no authentic portraits of Tiradentes made during his lifetime. The images we know were created later, already in the republican period. This absence allowed for a "reimagining" of his figure to suit the purposes of the new republic.

The influence of Pedro Américo's painting: Pedro Américo's painting "Tiradentes Supliciado" (Tiradentes Martyred) from 1893 is one of the most iconic representations of Tiradentes. In this painting, the resemblance to the traditional iconography of Jesus Christ is striking: long beard, long hair, suffering gaze, and a martyred body. This work played a fundamental role in fixing this image in the popular imagination.

The symbolism of sacrifice: The figure of Jesus Christ is central to the Christian tradition as a martyr who sacrificed himself for humanity. By associating Tiradentes with this image, the republicans sought to confer a redemptive meaning to his death for the Brazilian nation, elevating him to a level of sacrifice for freedom and the homeland. The proximity of his execution date (April 21st) to the celebration of Easter unconsciously reinforced this analogy of sacrifice.

The intention to create a pantheon of heroes: The First Republic invested in creating a pantheon of national heroes to consolidate the new regime. Tiradentes, with his history of struggle against the old order and his tragic end, became a key piece in this project of building a republican national identity. The similarity to religious figures helped to confer an aura of sanctity and legitimacy to this new hero.

In summary, the image of a bearded Tiradentes with features similar to Jesus, especially in a context close to Easter, is not a coincidence. It was a deliberate strategy by the nascent Republic to create a secular martyr, a hero whose sacrifice could inspire and unite the nation around republican ideals, using religious archetypes deeply rooted in Brazilian culture. Studies by art and visual culture historians, as well as analyses of the political discourse of the time, corroborate this interpretation.

PEDRO AMÉRICO

Hero or Invention?

The figure of Tiradentes, as taught and celebrated in Brazil, is undeniably a historical construct. Although his participation in the Minas Conspiracy is a fact, the transformation of a financially struggling junior officer into a national hero is the result of a process of selection, interpretation, and exaltation of certain aspects of his history to the detriment of others. Far from diminishing the importance of the Minas Conspiracy as a landmark in the history of the struggle for independence, recognizing the complexity of the figure of Tiradentes and the reasons behind his rise as a national hero allows for a richer and more critical understanding of our past. He thus becomes not just an idealized martyr, but a multifaceted historical figure whose trajectory reflects the tensions and political projects that shaped the Brazilian nation.

The Persistent Fact of History

The motivation behind the Minas Conspiracy (Inconfidência Mineira), rooted in exasperation with the Portuguese Crown's predatory fiscal policy and the looming "derrama" (forced tax collection), eerily echoes contemporary discussions surrounding Brazil's significant tax burden. Back then, the Portuguese metropolis exploited Minas Gerais, the colony's primary economic engine, through suffocating taxes on gold extraction. This fueled a sense of revolt among the local elite, who watched their resources drain away to support the kingdom's coffers. The "derrama," in particular, represented the pinnacle of this exploitation, threatening the economic stability and property of the colonists.

Similarly, modern Brazil grapples with a constant debate over the complexity and high tax load imposed by the government across its various levels. Business owners and citizens frequently express frustration with the substantial portion of their income and production allocated to taxes, fees, and contributions, often without perceiving a proportional return in quality public services. This perception of an excessive burden, which at times hinders economic growth, job creation, and consumer purchasing power, harkens back to the discontent that ignited the Minas Conspiracy.

Brazil's history appears marked by this recurring tension between the state's need to raise revenue and the limits of society's ability to contribute. From the colonial period, with the exploitation of brazilwood, sugar, and gold, to the present day, the issue of taxes and their application has been a central point of debate and, at times, conflict. The Minas Conspiracy, in this context, emerges as a historical example of how the perception of unjust and excessive taxation can catalyze movements of protest and the search for political alternatives. While collection methods and mechanisms have evolved significantly, the essence of dissatisfaction with a tax burden deemed oppressive persists as a relevant theme in Brazil's history.